China's PIPL and DSL

Comply with the PIPL and DSL

The Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) was adopted by the 30th meeting of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (NPC) and entered into effect on November 1, 2021.

The PIPL is a comprehensive data protection law that regulates personal information handling activities and promotes the rational use of personal information. It establishes duties for data controllers, such as the appointment of personal information protection officers, and includes provisions on conducting personal information protection impact assessments, as well as restrictions on international data transfers, among other things. The PIPL provides individual rights similar to those found in the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) (GDPR), including the right to know, access, data portability, refuse decisions made solely through automated methods, and request correction as well as deletion.

The Data Security Law (DSL) was passed on June 10, 2021, and entered into effect on September 1, 2021. The DSL regulates data processing activities associated with personal and non-personal data and introduces data security protection obligations for information processors including the designation of persons responsible for data security, the establishment of data security management bodies, and the conducting of risk assessments, among other things.

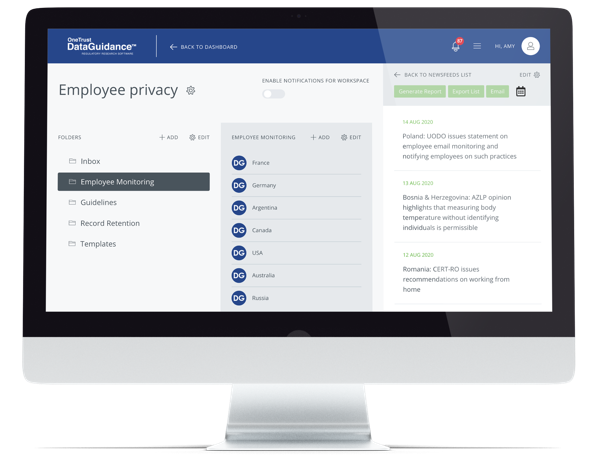

OneTrust DataGuidance's PIPL and DSL Portal provides you with the ability to track developments and understand the obligations under both laws.

Visit our China Jurisdiction Dashboard for further information on China's Data Protection Landscape.

Key Resources

China: PIPL overview – Key principles: Part one

The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (NPC) announced, on August 20, 2021, the adoption of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL). In Part 1 of this series, OneTrust DataGuidance discusses the PIPL and some of its provisions.

Introduction

The PIPL is China's first comprehensive data protection legislation and aims to protect personal information rights and interests, regulate personal information handling activities, and promote the rational use of personal information. The PIPL entered into effect on November 1, 2021. As part of a three-part series on the PIPL, this article intends to highlight key provisions, focusing on the fundamental principles established in the PIPL, as well as important definitions and explanations on the grounds on which the handling of personal information may be based.

Scope of application

General scope and exemption (Articles 3 and 72)

The PIPL clarifies that it applies to the personal information handling of natural persons within the People's Republic of China (PRC). In addition, the PIPL will also apply to the handling of personal information of natural persons within the PRC, that is conducted outside the PRC, where personal information is handled:

- for the purpose of providing products or services to natural persons within the territory;

- to analyze and assess the conduct of natural persons within the territory; and

- in other situations provided for by law or administrative regulations.

Please note that the PIPL does not apply to natural persons handling personal information for personal or family affairs.

Key definitions

The following definitions are set out in Articles 4, 28, and 73 of the PIPL.

Personal information: Any type of information that identifies or can identify natural persons recorded electronically or by other means but does not include anonymized information.

Handling of personal information: The collection, storage, use, processing, transmission, provision, disclosure, deletion, etc. of personal information.

Sensitive personal information: Personal information that once leaked or illegally used can easily cause natural persons to suffer encroachments on their dignity or harms to their persons or property; including information such as on biometric identifiers, religious faith, particular identities, medical care and health, financial status, and location tracking, as well as the personal information of minors under the age of 14.

Personal information handlers: Organizations or individuals that independently make decisions about the purposes and methods of personal information handling in personal information handling activities.

Automated decision-making: The use of computer programs to automatically analyze, evaluate, and make decisions on personal information on personal behavior habits, hobbies or economic, health, credit status, and so forth.

De-identification: The process of handling personal information to make it impossible to identify a specific natural person without the help of additional information.

Anonymization: The process in which personal information is handled so that it cannot be used to identify a specific natural person and cannot be restored after being so handled.

General principles

The PIPL establishes several principles that must be complied with when processing personal information.

Personal information processing principles (Articles 5 to 9)

When handling personal information controllers must respect the principles of legality, propriety, necessity, and creditworthiness, and not use misdirection, fraud, or coercion in personal information handling.

Further to the above, the PIPL stipulates that personal information handling must comply with the purpose specification, use limitation, transparency, quality, and accountability principles. More specifically, the PIPL provides that personal information handling must have a clear and reasonable purpose and employ the means with the smallest impact on individuals' rights and interests. In addition, the handling of personal information must comply with the principles of openness and transparency and responsible parties must ensure the quality of the personal information including ensuring that information is accurate or complete personal information. Moreover, controllers are responsible for their personal information handling activities and must employ necessary measures to ensure the security of the handled personal information.

Retention and storage limitation (Article 19)

The PIPL stipulates that personal information must be retained for the shortest time necessary to achieve the purposes of handling except as otherwise provided by laws and regulations.

Prohibition against illegal processing and processing endangering national security and public interest (Article 10)

The PIPL establishes a general prohibition on illegal processing that endangers national security and/or the public interest. More specifically, the PIPL stipulates that organizations and individuals must not unlawfully collect, use, process, or transfer the personal information of others; must not unlawfully buy, sell, provide, or disclose others' personal information; and must not engage in personal information handling activities that endanger national security or the public interest.

Lawful processing

Legal bases (Articles 13 to 15)

The PIPL, similar to the General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) (GDPR), outlines the legal bases for the processing of personal information. Specifically, the PIPL states that personal information handlers can only handle personal information where one of the following circumstances is met:

- the individual's consent is obtained;

- as necessary to conclude or perform on a contract to which the individual is a party, or as necessary for carrying out human resource management in accordance with lawfully formulated labor rules systems and lawfully concluded collective contracts;

- as necessary for the performance of legally prescribed duties or obligations;

- as necessary to respond to public health incidents or to protect natural persons' security in their lives, health, and property in an emergency;

- handling personal information within a reasonable range in order to carry out acts such as news reporting and public opinion oversight in the public interest;

- for a reasonable scope of handling of personal information that has been disclosed by the individual or otherwise already legally disclosed in accordance with this Law; and

- other situations provided by laws or administrative regulations

In relation to personal information handling on the basis of consent, the PIPL stipulates that consent must be given voluntarily and explicitly by individuals who are fully informed. In addition, where laws and administrative regulations provide that independent or written consent must be obtained for the handling of personal information, such provision must be followed. Moreover, where there are changes to the purpose or methods of information handling, or to the type of personal information to be handled, consent must be obtained again. Furthermore, individuals have the right to withdraw their consent, and the method for such withdrawal must be convenient and easy. The withdrawal of the individuals' consent does not, however, impact the validity of personal information handling activities conducted before the withdrawal.

Information sharing and disclosure (Articles 25 and 27)

The PIPL prohibits controllers from disclosing the personal information they handle, unless they have obtained consent or as otherwise provided for by laws and administrative regulations. However, controllers may process personal information disclosed by the individual themselves or that has been legally disclosed within a reasonable scope, unless the individual expressly refuses. Nevertheless, where personal information handlers handle disclosed personal information that has a significant impact on personal rights and interests, they shall obtain personal consent in accordance with the provisions of the PIPL.

Sensitive personal information (Articles 28 to 32)

The PIPL provides that controllers may only handle sensitive personal information for specified purposes and when fully necessary, and when employing strict protective measures. Please see above for the definition of sensitive personal information. Further to the above, controllers handling sensitive personal information must obtain independent consent, and where laws and administrative regulations provide obtained written consent for the handling of sensitive personal information. Moreover, when handling sensitive personal information, controllers must, in addition to the notification requirements specified in Article 17 of the PIPL, notify individuals of the necessity of sensitive personal information handling and the impact on the individuals' rights and interests, except where this Law provides that that notice need not be provided to individuals.

Personal information of minors (Article 31)

In relation to the personal information of minors, the PIPL stipulates that those handling the personal information of minors under the age of 14 online must obtain the consent of the minors' parents or other guardians. In addition, special rules for the handling of such data must be developed.

Conclusion

This article highlighted some of the key principles established in the PIPL. Part two will discuss controller obligations.

Keshawna Campbell Lead Privacy Analyst [email protected]

Karan Chao Privacy Analyst [email protected]

China: PIPL overview – Ensuring compliance: Part two

The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (NPC) announced, on August 20, 2021, the adoption of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL). In Part 2 of this series, OneTrust DataGuidance discusses the controller obligations that are key to ensuring compliance.

Introduction

The PIPL is China's first comprehensive data protection legislation and aims to protect personal information rights and interests, regulate personal information handling activities, and promote the rational use of personal information. The PIPL entered into effect on November 1, 2021. Similar to Part one of this three-part series on the PIPL, this article intends to highlight key provisions in the PIPL, focusing on the obligations of controllers necessary to ensure compliance with the PIPL.

Outsourcing and vendor management

Joint controllers (Article 20)

Where two or more entities jointly determine the purpose and manner of personal information handling, the PIPL stipulates that these entities should agree on their respective rights and obligations. Nevertheless, it should be noted that such agreements do not affect the exercise of individual rights, and joint controllers may be held jointly and severally liable for violations of the PIPL.

Processors (Article 21)

The PIPL outlines several obligations when outsourcing or entrusting handling activities to processors and third parties. In particular, by way of an agreement, the controller should stipulate: the purpose, duration, and manner of the handling, the type of personal information involved, any protection measures, and the rights and obligations of both parties. In turn, the processor must handle personal information in compliance with the agreement and never beyond the agreed purpose and manner. In the event that the agreement is deemed void or has been terminated, the PIPL clarifies that the processor is not permitted to retain the personal information and must either return or delete the same.

Controller obligations

Personal information protection program (Article 51)

As part of their duties under the PIPL, controllers are expected to implement a number of measures to ensure that handling activities comply with laws and regulations and prevent unauthorized access, disclosure, tampering, and loss of personal information. In line with the specific operations of the controller, and with the risk-based approach, such measures include:

- developing an internal management system and operating procedures;

- classifying and managing personal information;

- adopting appropriate security measures, such as encryption and de-identification;

- determining the operating limits for personal information handling, and regularly conducting education and training for employees;

- formulating security incident response plans; and

- other measures provided in law or regulations.

Designating representatives (Articles 52 and 53)

The PIPL requires controllers that handle personal information within thresholds prescribed by the Cybersecurity Administration of China (CAC) to appoint a person in charge of personal information protection, responsible for supervising handling activities and the protection measures taken. Separately, foreign controllers must establish a dedicated entity or designate a representative within the People's Republic of China (PRC) to deal with matters relating to the protection of personal information. The appointment of a personal information protection officer or, in the case of foreign controllers, the establishment of a designated entity or representative must be notified to the responsible State authority.

Auditing, assessing risk, and record-keeping (Articles 54 to 56)

Controllers are obliged to conduct regular compliance audits of their handling operations in accordance with laws and administrative regulations. Under the PIPL, controllers are also required to conduct a prior Personal Information Protection Impact Assessment (PIPIA), as well as record the processing activities, in the following scenarios:

- when handling sensitive personal information;

- when making use of personal information in automated decision-making;

- when entrusting the handling of personal information, or otherwise disclosing the same, to other entities;

- when transferring personal information overseas; or

- other handling activities that have a significant impact on the interests of individuals.

The PIPL clarifies that PIPIA reports and records of processing should be kept for at least three years. PIPIA reports, in particular, should document whether the purpose and manner of handling personal information is lawful, legitimate, and necessary; the impact on individual interests and any risks; and whether risk-based protective measures have been adopted.

Notifying data breaches (Article 57)

Where personal information has been disclosed, altered, or lost, or is likely to be, the controller must immediately take remedial measures and notify the responsible State authority and affected individuals. The PIPL specifies that notification should include:

- the controller's contact information;

- the types of personal information involved, as well as the causes and possible risks of the breach; and

- remedial measures taken by the controller and mitigation measures that may be taken by individuals.

However, notification to affected individuals may not be required where the controller has taken measures that effectively avoid any harm created by the breach unless otherwise required by the responsible State authority.

Internet platforms (Article 58)

In addition to the general obligations outlined above, the PIPL specifically targets internet platform services. More specifically, controllers of significant services, with a large number of users and a complex business model, are subject to the following requirements:

- to establish compliance systems and structures for the protection of personal information in accordance with State regulations, as well as an independent body to supervise the protection of personal information;

- to comply with principles of openness, fairness, and justice, establish rules for the platform, and clarify standards for the handling of personal information by product or service providers within the platform and the obligation to protect personal information;

- to stop providing services to product or service providers in platforms that seriously violate laws and administrative regulations; and

- to issue periodic reports on social responsibility and accept social supervision.

Transferring personal data overseas (Articles 38 and 39)

In terms of cross-border data transfers, the PIPL provides several mechanisms for transferring personal information. Personal information may be transferred under the following conditions:

- where a security assessment organized by the CAC is conducted;

- after undergoing personal information protection certification carried out by a specialized institution;

- where the controller has entered with the recipient into a standardized contract established by the CAC; or

- as stipulated by laws, administrative regulations, and other conditions by the CAC.

Furthermore, international agreements may be concluded, or acceded to, by the PRC, which may entail further conditions for cross-border transfers. More importantly, entities are required at all times to ensure that the activities of the recipient meet the standards set forth in the PIPL. In addition, entities must inform individuals and obtain their consent to the transfer. Information to be provided to individuals must include the name and contact information of the recipient, the purpose of processing, the type of personal information, and the methods of exercising his or her rights under the PIPL with the recipient.

As noted above, cross-border data transfers are also subject to a PIPIA under the PIPL.

Data localisation (Article 40)

In addition to the aforementioned conditions applicable to cross-border data transfers, the PIPL also establishes data localization requirements. Operators of critical information infrastructure, and entities that handle personal information within certain thresholds prescribed by the CAC, are required to store information that is collected and generated within the PRC domestically. Where it is necessary to transfer such information overseas, the controller must conduct a security assessment organized by the CAC, unless otherwise exempted by the CAC.

Conclusion

This article highlighted some of the obligations the PIPL introduces for controllers. Part three will discuss enforcement and individual rights.

Keshawna Campbell Lead Privacy Analyst [email protected]

Karan Chao Privacy Analyst [email protected]

China: PIPL Overview – Enforcement and Individuals' Rights: Part three

The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (NPC) announced, on August 20, 2021, the adoption of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL). In Part three of this series, OneTrust DataGuidance discusses individual rights and enforcement.

Introduction

The PIPL is China's first comprehensive data protection legislation and aims to protect personal information rights and interests, regulate personal information handling activities, and promote the rational use of personal information. The PIPL entered into effect on November 1, 2021. Similar to Parts one and two of this three-part series on the PIPL, this article intends to highlight key provisions in the PIPL, focusing on the rights of individuals and the enforcement of the PIPL.

Individuals' rights

The PIPL provides for a number of rights for individuals whose personal information is handled by controllers. In general, an individual has the right to know and determine the handling of their personal information, as well as to restrict or reject such processing, except as otherwise provided in laws and administrative regulations. In this regard, the PIPL establishes additional provisions pertaining to the following rights.

Right to be informed (Articles 17, 18, 30, and 48)

Content of information

Prior to the handling of personal information, the PIPL requires controllers to inform individuals truthfully, accurately, and fully of the following matters in clear and understandable language:

- the name and contact information of the controller;

- the purpose and manner of handling personal information, the type of personal information involved, and the retention period;

- the ways and procedures for individuals to exercise their rights under the PIPL; and

- other matters to be communicated under laws and administrative regulations.

Where a change occurs in the aforementioned matters, controllers are expected under the PIPL to inform the individual of such change. More generally, where the controller provides the required information by means of rules for the handling of personal information, such rules must be kept public and easily accessible.

Exceptions

Notwithstanding the above, controllers are not required to notify individuals in the case where laws or administrative regulations provide so or otherwise stipulate that personal information should be kept confidential. Furthermore, in an emergency, where it is not possible to inform the individual in a timely manner in order to protect an individual's life, health, or security of their property, controllers should notify the individual promptly after the elimination of the emergency.

Other matters to be notified

Separately, controllers must notify individuals and provide certain information where information is transferred to third parties. In terms of sensitive personal information, in addition to the matters outlined above, controllers must also inform individuals of the necessity of handling such information, as well as the impact on his or her rights and interests. Finally, the PIPL also confers the right of individuals to request an explanation of the rules governing the processing of personal information.

Right of access and data portability (Article 45)

An individual has the right to access and receive a copy of their personal information from a controller, which the controller must provide promptly upon request. However, controllers are exempted from complying with this obligation where laws or administrative regulations provide so or otherwise stipulate that personal information should be kept confidential. If the individual requests the transfer of personal information to their designated controller, the controller is obliged to provide the means of transfer if they meet the conditions prescribed by the Cybersecurity Administration of China (CAC).

Right to rectification (Article 46)

If an individual discovers that their personal information is inaccurate or incomplete, they have the right to request the controller to correct or complete their information. The PIPL clarifies that where an individual requests the correction or supplementation of their personal information, the controller is required to verify the personal information and correct and supplement it in a timely manner.

Right to erasure (Article 47)

The PIPL establishes that controllers should actively delete personal information under certain circumstances and, where a controller fails to do so, the individual has the right to request deletion.

These circumstances include:

- the purpose of handling has been achieved, is impossible to achieve, or is no longer necessary for the purpose of handling;

- the controller has ceased the provision of the product or service, or the retention period has expired;

- the individual has withdrawn their consent;

- the handling of personal information violates laws, administrative regulations, or agreements; and

- other circumstances prescribed by laws and administrative regulations.

Nevertheless, if the retention period prescribed by law or administrative regulations has not expired, or the deletion of personal information is technically difficult to achieve, the controller is expected to instead stop the handling, except for storage and taking necessary security measures.

Right to withdraw consent (Article 15)

Where the individual consents to the handling of personal information pursuant to Article 13 of the PIPL, the individual has the right to withdraw their consent. The PIPL stipulates that controllers should provide an easy means of withdrawing consent, and the withdrawal of consent by the individual shall not affect the effectiveness of the handling activities carried out prior to the withdrawal.

Rights of the deceased (Article 49)

Where a natural person dies, the PIPL permits their close relatives to, for their own lawful and legitimate interests, exercise the right to access, correct, and delete the relevant personal information of the deceased, unless otherwise arranged before the death of the deceased.

Procedure requirements (Article 50)

Controllers should establish convenient mechanisms for the processing of applications by individuals exercising their rights. If a request is refused, the reasons thereof must be provided to the individual. In addition, the PIPL confirms that where a controller rejects a request, the individual may file a lawsuit with a People's Court in accordance with law.

Duties of responsible State authorities (Articles 60 to 64)

At the national level, the CAC is responsible for the overall coordination of personal information protection and related supervision and management. Furthermore, the relevant departments of the State Council of the People's Republic of China are also responsible for the protection, supervision, and administration of personal information within their respective areas of responsibility, in accordance with the PIPL and other relevant laws and administrative regulations. At the local level, such duties of protection, supervision, and administration of personal information are determined in accordance with the relevant provisions of State regulation.

Duties of responsible State authorities

Under the PIPL, responsible State authorities are expected to fulfill the following duties:

- carrying out personal information protection publicity and education, and directing and supervising controllers to carry out personal information protection work;

- receiving and handling complaints and reports relating to the protection of personal information;

- organizing assessments of personal information protection, such as procedures, and publishing the results;

- investigating and handling unlawful handling activities; and

- other duties prescribed by laws and administrative regulations.

Role of the CAC

In addition to the duties outlined above, the CAC is authorized to:

- establish specific rules and standards for the protection of personal information;

- formulate special rules and standards for small-scale controllers, the processing of sensitive personal information, as well as new technologies and applications such as facial recognition and artificial intelligence;

- support the research, development, and promotion of the application of electronic identification technology and the establishment of public services for network identification;

- promote the establishment of systems for personal information protection, support relevant institutions in carrying out Personal Information Protection Impact Assessments and certification services; and

- improve mechanisms for complaints and reporting.

Supervisory authority measures

The PIPL empowers responsible State authorities to take a number of measures against controllers in fulfilling their duties. This includes:

- enquiring about the parties concerned and investigating the circumstances relating to the handling activities;

- inspecting and copying contracts, records, accounts, and other relevant information relating to the handling activities of the parties;

- carrying out on-site inspections to investigate suspected unlawful handling activities; and

- inspecting equipment and articles related to handling activities. Where there is evidence that the equipment and articles have been used to engage in unlawful handling activities, the authority may seize or confiscate such equipment and articles, following approval from their department.

In such cases, where a responsible State authority performs its duties according to the law, the party concerned are obliged to assist and cooperate and may not refuse or obstruct the same. More importantly, the responsible State authority may also interview the legal representative or the principal person in charge, pursuant to prescribed authority and procedure, or require the controller to engage a specialized institution to conduct a compliance audit. Thereafter, controllers must take measures as required to correct or eliminate any risks. Finally, the responsible State authority may refer persons, who are in violation of the PIPL in connection with a suspected crime, to the public security organs of the People's Republic of China.

Enforcement of the PIPL

The PIPL provides several methods for the enforcement of its provisions. As will be examined below the PIPL can be enforced by individuals, organizations, as well the relevant regulatory authority, and legally designated consumer protection organizations, among others.

Right to complain (Article 65)

The PIPL states that all organizations and individuals have the right to complain or report to the department illegal personal information processing activities. To this end, the departments receiving the complaint or report must promptly handle it in accordance with PIPL and notify the complainant or informant of the outcome.

Monetary penalties (Article 66)

The PIPL stipulates that where personal information is handled in violation of its provision, or personal information is not handled in compliance with personal information protection obligations the following may be imposed: correction order, issuance of warnings, the confiscate of unlawful gains; or an order to suspend or stop provisions of services. In addition, a fine of up to RMB 1 million (approx. €131,300) may be imposed; and a fine of between RMB 10,000 (approx. €1,300) and RMB 100,000 (approx. €13,100) issued to the directly responsible managers and other directly responsible personnel.

Further to the above, where the circumstances outlined above are serious, the relevant department will issue correction orders, confiscate unlawful gains, and give a concurrent fine of up to RMB 50 million (approx. €6.5 million) or up to 5% of the preceding year's business income. Moreover, such departments may order the suspension of the operation, suspension of the operations for rectification, or report to relevant regulatory departments for the cancellation of business permits or licenses. Finally, directly responsible managers and other directly responsible personnel may be fined between RMB 100,000 (approx. €13,100) and RMB 1 million (approx. €131,300) and a decision may be made to prohibit their serving as the board member, supervisor, senior management, or person in charge of personal information protection for an enterprise during a set period.

Liability for damages (Article 69)

Where personal information handling infringes on rights and interests in personal information and causes harm, and it cannot be proven that the personal information processor is not at fault, they will be liable to compensate losses.

Administrative fines and criminal responsibility (Article 71)

The PIPL establishes that where a violation of its provision constitutes a violation of the administration of public security, public security administrative sanctions are issued in accordance with law, and where a crime is constituted, criminal responsibility is pursued in accordance with law.

Legal action (Article 70)

Where personal information handlers violate the PIPL's provisions in their handling of personal information and infringe on the rights and interests of many individuals a lawsuit may be filed in the People's Court by the legally designated consumer protection organizations, and organizations designated by the CAC.

Conclusion

This article highlighted some of the key provisions on individual rights and enforcement in the PIPL. For an overview of key principles and controller obligations, see Parts 1 and 2 respectively.

Keshawna Campbell Lead Privacy Analyst [email protected]

Karan Chao Privacy Analyst [email protected]

OneTrust DataGuidance provides a means of analyzing and comparing data protection requirements and recommendations under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL). The report examines and compares the scope, main definitions, legal bases, data controller and processor obligations, data subject rights, and enforcement capacities of the PIPL with the GDPR.

You can access the latest version of the report here.

Key highlights

The PIPL and the GDPR share some similarities, particularly in regard to their material and territorial scope. Both laws:

- provide a legal basis for the lawful processing of personal information;

- require the conducting of data protection impact assessments;

- require the appointment of a data protection officer;

- require organizations to implement appropriate security measures with respect to personal information;

- provide special protections for the processing of minors' personal data;

- impose monetary penalties for non-compliance; and

- provide supervisory authorities with investigatory and corrective powers.

However, despite their similarities, PIPL and the GDPR also differ sometimes in their approach, such as:

- restrictions associated with the cross-border transfer of personal data;

- requirements for the maintenance of records of data processing activities;

- the liability of entrusted parties; and

- the GDPR permits processing for scientific research purposes and limits data subject rights in specific circumstances when processing for these purposes, while the PIPL does not.

China's Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) was first introduced in October 2020. Following two rounds of public comments, the finalized version was approved on August 20, 2021, by the National People's Congress (NPC) and entered into effect on November 1, 2021. Across the three drafts, notable changes were made including a right to data portability and enhanced protections for minors. OneTrust DataGuidance highlights the key difference between the three versions.

Please note that x indicates that this concept did not exist in the relevant version and ✓ indicates that there has been no notable change across drafts.

Concept | First Draft | Second Draft | Final Draft |

Constitution | x | x | Article 1 of the PIPL states the PIPL is enacted in accordance with the Constitution […]. |

Data quality | x | Article 8 of the PIPL introduced a requirement to ensure the quality of personal information to avoid adverse effects on personal rights and interests caused by inaccurate and incomplete personal information. | ✓ |

Lawful bases | Article 13 of the PIPL outlined lawful bases for processing. | Article 13 introduced a new lawful basis for processing where personal information has been made public and is processed within a reasonable range in accordance with the provisions of the PIPL. | Article 13 of the PIPL expands on the lawful bases of necessary for the conclusion or performance of a contract to include: where necessary to conduct human resources management in accordance with lawfully formulated labour rules and structures; and lawfully concluded contracts.

In addition, the PIPL establishes that personal information can be processed when handling personal information disclosed by persons themselves or otherwise already lawfully disclosed, within a reasonable scope in accordance with the provisions of the PIPL. |

Children | Article 15 of the PIPL required personal information handlers to obtain the consent of the minor's guardian when processing the personal information of those under the age of 14. | Article 15 of the PIPL expanded to include 'the minor's parent or other guardians.'

| Article 31 of the PIPL establishes that personal information handlers must also formulate special personal information processing rules for processing the personal information of minors under the age of 14. |

Withdrawal of consent | Article 16 of the PIPL provides a right to withdraw consent. | Article 16 of the PIPL clarifies that personal information handlers must provide a convenient way to withdraw consent.

In addition, the PIPL states that rescinding of consent does not affect the effectiveness of personal information handling activities undertaken based on individual consent before consent was rescinded. | ✓ |

Automated decision -making | Article 25 of the PIPL established rules for the use of automated decision-making including transparency and fairness. | ✓ | Article 24 of the PIPL expands on such rules, adding that where personal information handlers use personal information to make automatic decisions, it must not impose unreasonable differential treatment on individuals in terms of transaction conditions such as trade prices etc. |

Sensitive personal information | Article 29 of the PIPL established requirements for the processing of sensitive data which referred to personal information that may lead to discrimination or serious harm to personal or property safety once leaked or illegally used, including such information as race, ethnicity, religious belief, personal biological characteristics, medical health, financial accounts, and personal whereabouts.

| ✓ | Article 29 of the PIPL expands the definition of sensitive personal information to: personal information that, once leaked or illegally used, may easily cause harm to the dignity of natural persons grave harm to personal or property security, including information on biometric characteristics, religious beliefs, specially designated status, medical health, financial accounts, individual location tracking, etc., as well as the personal information of minors under the age of 14. |

Cross-border data transfers | Article 38 of the PIPL provided a mechanism through which personal information can be transferred abroad.

| Article 38 of PIPL expands on the basis of concluded contract to clarify such contract must be in accordance with the standard contract formulated by the Cyberspace Administration of China ('CAC'). | Article 38 of the PIPL removes the stipulation that the conclusion of the contract must supervise the recipient's processing of personal information to ensure that the recipient's processing meets the standards for the protection of personal information as prescribed within the PIPL. In addition, Article 38 inserts 'where the international treaties and agreements that the PRC has concluded or participated in have provisions on the conditions for providing personal information outside the PRC, such provisions may be complied with.' |

Data portability | x | x | Article 45(2) of the PIPL states where individuals request that their personal information be transferred to a personal information handler they designate, meeting conditions of the CAC, personal information handlers shall provide a channel to transfer it. |

Deceased persons | x | Article 49 of the PIPL establishes that in the event of the death of a natural person, the rights of the individual in the personal information processing activities prescribed in Chapter IV shall be exercised by his next of kin. | Article 49 of the PIPL establishes the exception of the deceased having otherwise arranged before his/her death. |

Exercising Individual rights | Article 49 of the PIPL stipulated that personal information handlers must establish mechanisms for accepting individuals' requests and provide a reason for rejecting a request. | ✓

| Article 50 of the PIPL clarifies that the mechanism established for accepting individuals' request must be convenient. In addition, Article 50 establishes that where the personal information handler refuses an individual's request to exercise his rights, the individual may bring a lawsuit in a people's court according to law. |

Internet service providers | x | Article 57 introduces requirements for personal information handlers that internet platform services with a large number of users. | Article 58 of the PIPL further establishes that personal information handlers that internet platform services with a large number of users must also comply with principles of openness, fairness, and justice, establish rules for the platform, and clarify standards for the handling of personal information by product or service providers within the platform and the obligation to protect personal information. |

Entrusted parties | x | Article 58 of the PIPL establishes that parties entrusted to process personal information must fulfill the relevant obligations prescribed in Chapter V and take necessary measures to ensure the security of the personal information processed. | Article 59 of the PIPL expands entrusted parties responsibilities to include assisting personal information processors to fulfill their obligations under law . |

Personal liability | Article 62 of the PIPL outlined requirements for the penalties for where personal information is processed in violation of the provisions of the PIPL. | ✓

| Article 66 of the PIPL clarifies that liability will also apply where personal information is processed without fulfilling the personal information protection obligations stipulated in the PIPL. In addition, Article 66 expands the orders that can be taken by the departments performing personal information protection duties to include ordering the application that illegally processing personal information to suspend or terminate the provision of services. Furthermore, Article 66 establishes that where applicable persons may also be prohibited from serving as directors, supervisors, senior managers, and persons in charge of personal information protection of relevant enterprises for a certain period. |

Keshawna Campbell Lead Privacy Analyst [email protected]

China: The DSL and its organisational impact

The Data Security Law (DSL) made some significant additions to the Chinese legal framework on personal information and how it can be handled. Dr. Michael Tan and Julian Sun, Partner and Associate respectively at Taylor Wessing LLP, discuss the DSL's highlights and give some practical recommendations in order to prepare.

With the rapid development of online technology, personal information emerges as a more and more important resource which is profoundly affecting economic development and people's daily lives. However, the slow pace of legal reform makes data protection issues quite difficult to navigate, leaving room for data abuse which jeopardises public interest and even national security. To regulate these issues from a strategic level and further substantiate the data protection requirements under the Cybersecurity Law 2016 ('CSL'), the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress officially launched the DSL, which will take effect as of 1 September 2021. Below are some highlights worth noting.

'Long arm' approach

Due to the boundless nature of internet, extraterritorial administration of data-related activities concerning the interest of the People's Republic of China ('PRC') has always been a tricky issue to manage. Unlike the CSL, which only covers the construction, operation, maintenance, and use of the network within the territory of the PRC, Article 2 of the DSL now adopts a 'long arm' approach that covers data processing both onshore and offshore. As long as any offshore data processing activity harms national security, public interests, or the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese citizens or legal entities, such activities will also be pursued by Chinese authorities. This new development could be an alert to multi-national companies who collect data from China via their Chinese subsidiaries, while further processing of such data may be handled offshore by the headquarters or other service providers. Although such data processing mode is not completely prohibited by the DSL, it should be noted that due to the very broad concept of 'national security, public interests, and legitimate rights and interests of Chinese legal entities', processing PRC data offshore may very likely be caught by this concept, resulting in higher data compliance requirements under Chinese laws.

Disclosure to authorities

This is another sensitive topic regarding national security and public interest. Due to confidentiality concerns, it is not uncommon that multi-national corporations may not want to share their data with government authorities. This could change now under the DSL, which requires opening of access to Chinese authorities where necessary for national security or crime investigation purposes. Confidentiality could no longer be a good cause to refuse granting access, and non-cooperation could subject multi-national corporations to a fine up to RMB 500,000 (approx. €65,320) if they refuse to provide the requested access or data. On the other hand, the DSL also establishes obstacles for multi-national corporations to respond to data disclosure requests from any foreign law enforcement agencies or courts, with a request for data relevant to a foreign compliance or criminal case involving the China subsidiary of a multi-national corporation requiring prior approval by competent Chinese authorities. Illegal provision of data under such context could lead to suspension of business, a fine up to RMB 5 million (approx. €653,240), or even revocation of a business licence. Potential conflicts between different jurisdictions might arise in this context and multi-national corporations would need to take this into consideration when planning their global compliance scheme.

Data export control

Data export control requirements are addressed in the CSL, covering both personal information and important data and applying to so-called critical information infrastructure operators ('CIIO'). On top of these obligations, Article 31 of the DSL further expands the data export control requirement for important data to all 'data processors', which in general covers all legal entities who collect or generate important data within the PRC. Although the DSL leaves it to the administrative authorities to formulate more detailed rules to define and regulate important data export control, it is foreseeable that even stricter export clearance requirements such as mandatory security assessments will be required considering the higher sensitivity of important data. Presently how Article 31 of the DSL will be implemented in practice remains to be seen.

The concept of important data is something that does not exist under the General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) or other prominent data protection laws. More detail about this concept can be found under the draft national standards Information Security Technology - Guidelines for Data Cross-Border Transfer Security Assessment ('the Standards'), which further outlines what kind of data will be classified as concerning national security, economic development, and public interest. Examples given under the Standards include e.g. geographic data, biometric data, financial data, military data, and data of sensitive industries like utility, transportation, and nuclear industries. Although the Standards have not yet officially become effective, they may be used as a reference point to better understand the implications brought by the DSL that relate to the concept of important data, including how to better manage topics like important data export control. Against this background, multi-national corporations are encouraged to run an internal data mapping within their own organisation to identify important data as addressed by the DSL, and take necessary measures to prepare themselves for the foreseeable data export control requirement.

Data transaction

Although more and more market players view data as an important asset for their business, so far there is no explicit legal basis under Chinese law recognising data as tradable assets. The DSL sheds some positive light in this regard by stipulating in Article 19 that a data transaction administrative system shall be established to develop the market herein. In reality, several local data exchanges have already been established in some pilot cities to test the water even before such explicit legal basis at national law level becomes available. Data being traded in those exchanges could cover audience profile, credit risk profile, enterprise profile, artificial intelligence, etc. One may expect more business opportunities and possibilities on the Chinese data market in the foreseeable future, which, despite regulatory challenges brought by the DSL, could be a positive signal for multi-national corporations doing business in the Chinese market.

Conclusion

Driven by the protection of national security, economic development, and public interest, the DSL substantiates data protection legal regime in China from a more specific political angle. The wording of the DSL remains quite general and must be further substantiated by more detailed rules, as well as national standards to be promulgated in the future. But the major principles outlined by this law already indicate some significant data compliance challenges ahead for multi-national corporations, since in the foreseeable future they will need to manage different 'data border control' requirements that might arise under different jurisdictions. Below are some recommendable measures which one may already consider implementing so as to better prepare for the DSL's coming into force:

- data mapping within the organisation to better understand the potential loopholes and issues with special attention to be paid to any data exports;

- reviewing internal organisational set-ups and resources to ensure sufficient attention to and investment in data compliance topics; specifically, this not only includes technical means for ensuring data security, but also proper protocols and regular training of staff;

- compliance audits throughout the organisation, as well as on business partners; as far as data trading is concerned, implementing a proper Know Your Customer process is recommendable; and

- organising regular Data Protection Impact Assessments and ensuring good communications with the competent authorities, as well as putting in place a risk monitoring system and a contingency plan to manage potential security and data breach issues.

Dr. Michael Tan Partner [email protected]

Julian Sun Associate [email protected]

Taylor Wessing LLP, Shanghai

On April 26, 2024, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) announced the Telecommunications Service Quality in the first quarter of 2024.

In particular, the MIIT outlined, among others:

On April 15, 2024, the National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (TC260) requested public comments on the Draft National Standard Network Security Technology Information System Disaster Recovery Specifications.

On April 15, 2024, the National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (TC260) requested public comments on the Draft National Standard Implementation guide on cybersecurity operation and maintenance.

On April 15, 2024, the National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (TC260) requested public comments on the Draft National Standard Security Requirements for Data Security Technology and Government Data Processing.

On April 11, 2024, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) announced the release of the fifth batch of deep synthesis service algorithm registration information.

On April 3, 2024, the National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (NPC) announced that several NPC deputies proposed a bill on the preparation of a Digital Economy Promotion Law (the Law), to promote the modernization of the digital economy governance system and capabilities.

On April 3, 2024, the National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (TC260) requested public comments on the following draft standards:

On April 3, 2024, the National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (TC260) announced the release of a list by the National Standardization Administration Committee with eight recommended national standard projects for network security, including but not limited to:

On April 3, 2024, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) released a statement on China-Africa artificial intelligence (AI) cooperation following a China-Africa Internet Development and Cooperation Forum held in Xiamen, China, from April 2 to April 3, 2024.

On April 2, 2024, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) announced the release of registered information on generative artificial intelligence services, including a model name, filing entity, territory, and registration number.

On March 22, 2024, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) published the Regulations on Promoting and Regulating Cross-border Data Flows.

On March 22, 2024, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) published two updated guidelines, namely the Guidelines for the Declaration of Data Transfers Security Assessment (second edition) (the Assessment Guidelines) and the Guidelines for the Filing of Standard Contracts for the Transfer of Personal Information (second edition) (the Stand

On March 21, 2024, the National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (TC260) issued five recommended cybersecurity standards, including:

On February 27, 2024, the Zhejiang Provincial Communications Administration notified 12 apps of violations of users' rights and interests.

On February 21, 2024, the Hubei Provincial Communications Administration Bureau published a notice of its first batch of notifications to apps on violations of users' rights in 2024.

On February 1, 2024, the State Post Bureau requested comments on the Measures for the Security Management of Personal Information of Mail and Delivery Service Users. Comments were due to be submitted by March 2, 2024.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) published the Regulations on Promoting and Regulating Cross-border Data Flows (only available in Chinese here) (the Regulations) on March 22, 2024, following their initial request for public comment in October 2023.

In an era dominated by digital connectivity, safeguarding the integrity of networks and information systems has become a global imperative. China, recognizing the critical importance of cybersecurity, has introduced the draft Management Measures for Cybersecurity Incident Reporting (the Measures).

On October 15, 2023, the public comment period closed for the Cyberspace Administration of China's (CAC) draft Provisions on Regulating and Promoting Cross-Border Data Flows (the Draft Provisions). In this Insight article, Kate M. Growley, Evan Y.

The rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) in China has made it an important player on the global stage.

In many aspects, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which became effective on November 1, 2021, looks very similar to the EU's General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). However, many of these similarities remain as high-level principles under the PIPL, while more detailed content has been rolled out step by step.

Since 2021, in the wake of the Provisional Regulations on Data Security Management of the Automotive (the Automotive Data Regulations), and under the purview of China’s data protection legislation landmark legislations - the Data Security Law (DSL) and the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), data protection and cybersecurity concerns hav

As the digital economy continues to expand globally and the legal regimes of data protection vary in different jurisdictions, multinational companies carrying out cross-border data transfer activities face challenges in complying with multi-jurisdictional data protection regulations.

Part one of this series presents an overview of the Information Security Technology - Technical Requirements of Security Design for Cybersecurity Classification Protection (GB/T 25070-2019) ('the Security Design Requirements'),

On 24 February 2023, the Cyberspace Administration of China ('CAC') promulgated the finalised Standard Contract Measures for Exporting Personal Information1 ('the Measures'), along with the Personal Information Export Standard Contract ('the Standard Contract'). The Measures will take effect on 1 June 2023.

On 2 December 2022, the Communist Party of China ('CPC') Central Committee and the State Council jointly released the Opinions on Building Basic Systems for Data to Better Play the Role of Data Factors ('the Opinions'), in order to speed up efforts to build basic systems for data, give full play to China's strengths in massive-scale data and ric

On 24 February 2023, the Cyberspace Administration of China ('CAC') released the final form of its key transfer mechanism for data exports - the long-awaited Personal Information Export Standard Contract ('the Standard Contract') and its accompanying Measures on the Standard Contract ('the Measures'), which set out the principles governing the u

Great news from the Cyberspace Administration of China ('CAC') - China's Standard Contract Measures for Exporting Personal Information ('the SCC Measures') have been officially adopted by the CAC on 22 February 2023.