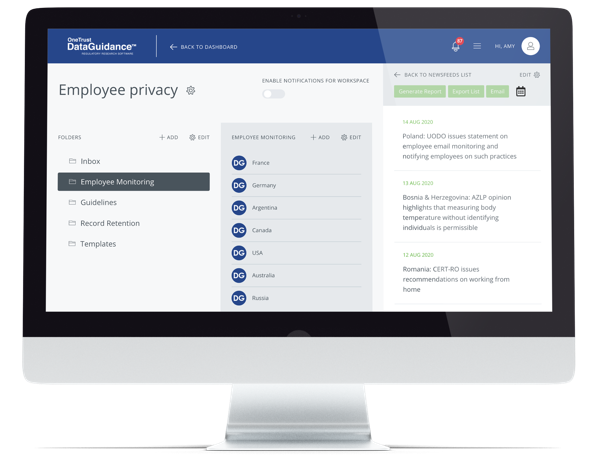

Continue reading on DataGuidance with:

Free Member

Limited ArticlesCreate an account to continue accessing select articles, resources, and guidance notes.

Already have an account? Log in

Japan: 'Personally referable information' under the APPI – is this personal data?

A new concept called 'personally referable information' was introduced into Japanese privacy law by the Act on Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of 2003 as amended in 2015) ('APPI') and came into effect from April 2022. But what is it? Kensaku Takase and Yuki Kondo, from Baker McKenzie, provide clarity on what 'personally referable information' is and what it means for companies.

What is 'personally referable information'?

Have you received a puzzling request or questionnaire from a Japanese company asking for information on whether you have received consent from data subjects for data you are receiving from them? It may be a customer of yours, or a supplier? This is one of the most frequent queries we are receiving these days and this article aims to help you understand what is going on.

The first thing to point out is that despite what you may think when hearing the term 'personally referable information', it is not personal data.

In the drafting stage of the APPI, the concept of 'personally referable information' was reportedly created to address the use of cookie data. However, the Personal Information Protection Commission ('PPC') clarified that this new type of regulation was not intended only for regulating the use of cookie data. Browsing history collected through cookie data would be a typical example of 'personally referable information' but the term can also cover consumers' purchase history and location data. This is because the collection, analysis, and use of such data may also raise privacy concerns.

Under Japanese privacy law, certain data, including cookie data, does not constitute personal data on its own. However, like many forms of data, it can become personal data if combined with other data that can identify a specific individual.

The legislators were aware that, in many situations a company which may have gathered such data may not itself know the identity of the data subject to whom the data relates. However, often companies that gather the non-personal data will sell such data to third parties. The legislators were worried that the third parties may be able to combine the non-personal data with other data sets in their possession, thereby transferring the non-personal data into personal data; despite the data subjects having no knowledge of this fact.

The other aspect the legislators were concerned about was data subject consent. Even before the introduction of the 'personally referable information' concept, Japanese privacy law generally required the consent of data subjects for transfers of personal data to third parties. However, the application of this requirement can be determined by whether the party transferring personal data can identify a specific individual based on the relevant personal data. The legislators were concerned about situations where the existing data transfer rule would not apply simply because the transferor could not identify an individual in its transferred data despite there being a risk of the recipient being able to do so.

'Personally referable information' rules were therefore created to fill in the gap in the law by requiring there to be steps to try to ensure there is consent from data subjects.

Examples of personally referable information in action

To illustrate this, here is an example of a scenario that is intended to be covered by the rules surrounding 'personally referable information': a data analytics company may be using cookies to track potential product preferences of visitors to an e-commerce site. As part of a contract with the e-commerce site operator, the data analytics company provides the cookie data to the e-commerce site operator, who has the ability to tie the visits to specific customers. The e-commerce site operator can then develop more targeted advertising to those customers based upon information gleaned from the cookie data.

Here the recipient (in our example the e-commerce site operator) is the only party who would know whether or not the data may be combined with other data to create personal data. This means that the recipient is required to obtain express consent from its data subjects (in our example, the e-commerce site customers). The transferor needs to confirm that this consent has been obtained before sharing the data with the recipient.

It is important to remember that the new rules do not apply to all transfers of personally referable information. They apply only when the transferor expects that the recipient will receive the 'personally referable information' to use it as 'personal data' by linking it with existing personal data of the recipient.

A party transferring personal data can imply that a recipient will not be creating personal data from the personally referable information. However, it will be the transferor's burden to prove this. To ensure there is certainty and a paper trail, often transferors simply ask the recipients for their confirmation in writing, hence the questionnaires that are often seen.

Recordkeeping obligations for personally referable information

For completeness, it is worth noting that there are also recording keeping obligations on the transferor and recipient. Both parties must create and keep a record of the transfers of personally referable information such as the name, the address and name of a representative of the transferor and recipient, the items of personally referable information, and a record that data subject consent was obtained by the recipient. For the transferor, such records must be kept upon the transferor's receipt of confirmation that the recipient has confirmed that the data subjects have provided their consent. For the recipient, a record must be made after receipt of the personally referable information from the transferor. While the retention period of these records may depend upon certain factors, the maximum retention period will be three years.

Consequences of non-compliance

So what are the potential penalties if there is a breach of the obligations surrounding personally referable information? Like all breaches under the Japanese privacy law, a breach of the personally referable information rules may potentially result in a fine of up to JPY 100,000,000 (approx. €714,600). However, Japanese privacy law adopts a phased enforcement approach. So, even if the PPC finds that a company has not complied with the law or rules, there will be an opportunity to remedy the situation. A fine will only be imposed when the company does not correct its non-compliant practices despite the PPC's enforcement warnings.

Next steps for companies

The first thing to do is to check if you will be transferring or receiving personally referable information to or from a third party. If you are a transferring party, you may need to create and send something like a questionnaire to confirm that the recipient has received the appropriate consents. If you are the recipient, you should consider arrangements to obtain consent from data subjects, which may be as simple as a check box on your website.

The legislators came up with the term 'personally referable information' which, from the confusion we have seen, is not the best term. What would we have called it instead? How about 'potential personal information'?

Kensaku Takase Partner

[email protected]

Yuki Kondo Associate

[email protected]

Baker McKenzie, Tokyo