Continue reading on DataGuidance with:

Free Member

Limited ArticlesCreate an account to continue accessing select articles, resources, and guidance notes.

Already have an account? Log in

Singapore: Approach to AI governance - multistakeholder-based pragmatism and enablement

In a time when competing approaches to artificial intelligence (AI) governance develop in different parts of the world, Singapore is charting a path that emphasizes pragmatism and enablement.

The National AI Strategy, a high-level strategy statement by the Singaporean government, envisions Singapore as a global hub for developing, test-bedding, deploying, and scaling solutions, with an additional focus on strengthening the country's AI ecosystem enablers. Since its publication four years ago, developments in Singapore's landscape of AI governance have been consistent with this approach, employing a decidedly 'light touch' in regulation and emphasizing the provision of practical tools and frameworks for responsible development and adoption. In this Insight article, Jeffrey Lim, Director at Joyce A. Tan & Partners LLC, will summarize Singapore's approach to AI governance in this context.

Context and contrasts

First, let's provide some context. Singapore's approach can be compared to two different approaches in Europe and China.

In Europe, the upcoming EU AI Act is set to establish a comprehensive legal framework that sets guidelines with the objective of strengthening rules around data quality, transparency, human oversight, and accountability, building on its focus on safety, fundamental rights, democracy, and the rule of law. The EU will consolidate enforcement of the AI Act into one agency per Member State whilst also looking into rules on liability for the use of AI.

In China, various agencies drive the thinking on regulation and oversight of AI, aimed at enabling bureaucratic and state oversight of AI deployment. These agencies have differing points of emphasis. The regulatory landscape in China appears to prioritize political and social stability, among other objectives, by implementing controls and targeting specific technologies and issues as they arise.

These approaches share significant similarities, despite their differences. In regulatory terms, both are characterized by an interventionist approach, where the state takes legislative action to influence outcomes.

From this perspective, two observations can help explain Singapore's approach:

- innovators and the business community may feel that such an interventionist approach could stifle innovation or impede competitiveness. In the EU for example, various European companies expressed concern over proposals for the AI Act; and

- any perceived loss of competitiveness due to excessive regulation might be more well tolerated by governments and economics with greater political, social, and economic influence.

Singapore sees itself as being different. Indeed, commentators have identified Singapore as a 'price-taker' rather than a 'price-setter' in matters of AI governance. While this does not mean that Singapore would not step into an interventionist mode, it does mean that the approach would need a compelling case for intervention.

Not much 'hard' law

This approach is evident in Singapore's inventory of measures in this regard.

For instance, when certain agencies such as the Personal Data Protection Commission (PDPC), Singapore's cross-sector privacy regulator, consider the Advisory Guidelines on the Use of Personal Data in AI Recommendation and Decision Systems, it should not be interpreted as a broad change in direction to regulate AI but rather, a cautious step forward to introduce incremental safeguards in areas where regulation already exists, notably under Singapore's national privacy law.

A review of the existing 'hard' law confirms this. There may be subsidiary legislation that addresses the trials of self-driving vehicles, the registration and governance of AI medical devices, which fall under the purview of telehealth and medical device regulations, as well as the aforementioned proposed PDPC guidelines in relation to personal data. Additionally, there may be a sector-specific instrument, such as circulars or notices, addressing the use of certain types of AI in regulated sectors.

Frameworks and tools

In contrast, there is more in the way of sectoral guidelines or guidance in areas such as healthcare, Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare Guidelines (AIHGle), or financial services, Principles to Promote Fairness, Ethics, Accountability and Transparency (FEAT) in the Use of Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytics in Singapore's Financial Sector, which establish expectations and standards within pre-existing regulatory frameworks.

Voluntary frameworks are key enabling tools, and Singapore has been a global leader in this regard, with its Model AI Governance Framework, developed by the Info-communications Media Development Authority (IMDA) and PDPC, which is now in its second edition.

Notably, the 11 governance principles identified in the Model AI Governance Framework (transparency, explainability, repeatability/reproducibility, safety, security, robustness, fairness, data governance, accountability, human agency, and oversight, along with inclusive growth, societal, and environmental well-being) do not break new ground in that they are well aligned to other publicized models. This firmly places Singapore in good company as far as emerging consensus on certain ethical norms is concerned. The framework translated these guiding principles into actionable areas:

- internal governance structures and measures;

- determinations of human involvement in AI-augmented decision-making;

- operations management; and

- stakeholder interaction and communication. This part of the framework is aptly titled 'From Principles to Practice.'

Singapore's emphasis on pragmatism and enablement meant that it was never going to settle on iterating the Model AI Governance Framework, and soon after the first edition was published, a practical companion to the framework, the Implementation and Self-Assessment Guide for Organizations (ISAGO) was released in January 2020. ISAGO compiles lists of guiding questions as a way of helping organizations conduct in assessing whether they are implementing the principles of the framework in a real and practical way. Other resources, intending to broaden the publicly available resources for understanding the use cases for AI, include the compendium of AI use cases.

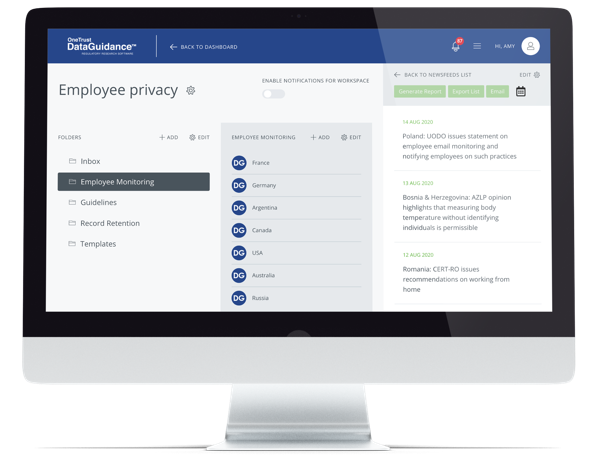

In line with this approach, the IMDA and the PDPC also launched AI Verify, an AI governance testing framework and toolkit. Having been launched after testing and feedback from the industry, AI Verify is designed to be a useful and implementable tool that can be applied by organizations that deploy AI.

Communities of practice

This approach to developing capabilities and practical competence has its precedent in Singapore. For example, the IMDA has worked with industry bodies such as the Singapore Computer Society (SCS) in developing the SCS Artificial Intelligence Ethics & Governance Body of Knowledge, which is aimed at professional communities of practice that execute technical implementation of AI solutions and serves as a valuable tool for upskilling and promoting familiarity with AI ethics to AI practitioners. Additionally, this body of knowledge and its syllabus provided the foundation for SCS's course and certification framework for AI ethics professionals.

The emphasis on communities of practice aligns with the thinking behind the establishment of the AI Verify Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation with the following stated goals:

- foster a community to contribute to the use and development of AI testing frameworks, code base, standards, and best practices;

- create a neutral platform for open collaboration and exchange of ideas on AI testing and governance; and

- nurture a network of AI advocates and drive broad adoption of AI testing through education and outreach.

When will more 'hard law' emerge?

Singapore's approach to AI governance, characterized by a light touch, voluntary framework, limited legislative intervention, and a focus on enablement and pragmatic implementation, stands out in that it avoids issuing broad legal directives or legislation with vague policy statements that require extensive further elaboration. However, a few observations can be made:

- there may be boundaries in the practice and use of AI developments and solutions that currently lack clear legal definitions. Legislative intervention may become necessary only when specific political, social, or economic harms emerge that cannot be resolved by applying or extending existing legislation. In essence, this would entail minimalist intervention; and

- the ongoing investment in frameworks and the development of practical tools may also help lead to future regulation. The development of frameworks, tools, competencies, and resources inevitably leads to the emergence of standards, norms, and actionable benchmarks against which conduct can be measured. This, in turn, could well provide the basis for legally enforceable standards.

On the first point, the issue of 'Deep Fakes' can be considered. Criminal laws on fraud, impersonation, and scams might be applicable to the use of AI by malicious actors for certain purposes. Laws addressing the propagation of online falsehoods might also be a tool for regulators to rein in the politically destabilizing use of technology. However, there are potential concerns related to proprietary rights, particularly in cases involving generative AI that displaces creators and their livelihoods. Existing intellectual property laws may not fully address these new economic arrangements being propelled by AI, suggesting a potential need for targeted legislative intervention in AI-related matters.

On the second point, this multi-stakeholder collaborative process could act as a way of democratically advancing discourse on what any law on AI could contain.

Generative AI

A notable example is how IMDA has approached the regulation of generative AI. While countries such as China have moved forward quickly with regulations (even to the potential detriment of its rivalry with the US), IMDA continues to move forward cautiously and consultatively. For example, they published a discussion paper through the AI Verify Foundation, outlining observations of the risks associated with generative AI, particularly:

- mistakes and 'hallucinations:' The susceptibility to errors or 'confabulation,' with insufficient skepticism from users;

- privacy and confidentiality: concerns related to the retention or handling of data and information in unintended ways;

- amplification disinformation, toxicity, and cyber-threats: The ability of generative AI to support the dissemination of fake news, support impersonation, reputation attacks, etc;

- copyright challenges: Including issues like the problematic scraping of proprietary content to train models and the potential displacement and disintermediation of authors, artists, or musicians, raising challenges about the subsistence of copyright and its ownership;

- bias: embedding or entrenching of biases inherited from the internet and pre-existing data; and

- harmful uses: when generative AI is put to uses that are not aligned with human values and goals.

In response to these risks, IMDA has indicated that policymakers should enable greater adoption and put in place guardrails to address the risks and ensure safe and responsible use. This approach places an emphasis on system application, holistic assessment of recommendations, and an iterative approach to policy. The signaled approach is described as practical, risk-based, and accretive with a focus on six dimensions:

- accountability, including a shared responsibility framework and the encouragement of standardized information disclosures on AI models with potential labeling or watermarking;

- data use, encompassing transparency, privacy, copyright issues, and addressing bias through collaborative efforts to build trusted data sources;

- model development and deployment, focusing on design choices by AI developers, and transparency on their development, testing, and performance, with the aim of building standardized evaluation metrics and tools;

- assurance and evaluation, involving the development of independent third-party evaluation and assurance mechanisms, including crowd in open-source expertise (via a vibrant open-source community);

- safety and alignment research;

- generative AI for public good, promoting consumer literacy through enhanced education and training, updating guidance for organizations, and developing common infrastructure to help the wider ecosystem to develop and test generative AI models and applications, while measuring the end-user impact of these models and applications.

The paper concludes by advocating collaboration to work towards a common global platform and improved governance framework.

Conclusion

If we categorize stakeholders impacted by AI into three groups: developers, users, and the general public, it becomes evident that we should also focus on Singapore's current approach in terms of the general public.

In this regard, investment in education as a policy lever is particularly important. This is to ensure that end users, individuals interacting with AI (as data subjects, customers, or even persons incidentally affected by the use of AI by organizations or developers) are in a position to request or implement safeguards.

But equally, this suggests that one potential future area of legislative intervention could well be the development of legislation aimed at promoting accountability and remedies for the public, benchmarked to evolving standards that emerge from the current state of AI governance.

That said, it's essential to consider Singapore's 'price-taker' status, as mentioned earlier. With the imperative to foster the growth of the AI development ecosystem, it remains an important part of Singapore's policy to ensure that its approach to AI governance does not prematurely stifle interest in the country as a place where innovation and adoption of AI are encouraged.

Determining when legislative intervention is necessary is simply a case of finding harm that cannot be sufficiently addressed in existing laws that bear characteristics peculiar or particular to AI and which manifests itself with sufficient gravity and frequency for intervention. This process requires careful consideration.

For the time being, Singapore proceeds with caution and pragmatism, setting itself apart from some larger countries in other parts of the world.

Jeffrey Lim Director

[email protected]

Joyce A. Tan & Partners LLC, Singapore