Continue reading on DataGuidance with:

Free Member

Limited ArticlesCreate an account to continue accessing select articles, resources, and guidance notes.

Already have an account? Log in

International: Diversity and inclusion surveys in APAC

Diversity and inclusion programmes are becoming increasingly popular across the globe due to a growth in awareness and a demand for organisations to support values, such as equity and inclusion. While actively engaging in diversity and inclusion initiatives may help organisations to better understand, manage, and develop the business, it is not always clear what data can, and cannot, be included in diversity monitoring surveys or what the rules are for such data collection.

The legal requirements surrounding information relating to an individual's race, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and health differ from country to country, with some classifying such data as 'sensitive data', while others view it under the umbrella of 'personal information'.

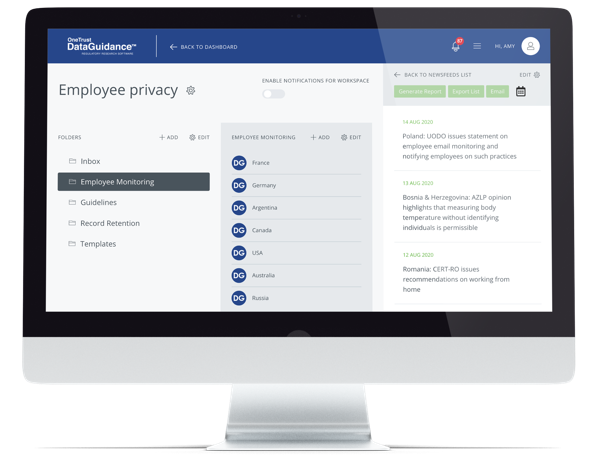

OneTrust DataGuidance Research has consulted with a number of legal experts operating within the Asia Pacific region in order to uncover the requirements for the collection and use of employee data for diversity and inclusion surveys. The countries covered in this Insight article include Australia, China, Singapore, Japan, Hong Kong, and India.

Australia

Katherine Sainty and Natasha Singh, Director and Graduate Lawyer respectively at Sainty Law, discuss what the privacy considerations are with regards to the collection of information for diversity surveys in Australia, as well as outlining the key takeaways from the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner's ('OAIC') guidance on data analytics.

Diversity surveys

In 2019, Diversity Council Australia conducted a survey1 of 3,000 Australian workers which revealed that 75% of them support their employer taking action to create a diverse and inclusive workplace. As such, diversity surveys have become an increasingly popular tool for employers to drive the diversity and inclusivity workers are after.

While the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) ('RDA'), coupled with the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) ('FWA'), make it unlawful for employers to treat an applicant or employee unfavourably by virtue of their race, colour, national, or ethnic origin (Section 9 of the RDA and Section 351 of the FWA), employment law generally does not prevent employers from conducting diversity surveys. For certain agencies and organisations, diversity data must be collected in accordance with the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) (No.119, 1988) (as amended) ('the Privacy Act').

Privacy considerations

Under the Privacy Act, information or an opinion about an individual's race, ethnicity, politic opinions, religion, sexuality, health, and genetic information is considered to be 'sensitive information'. Sensitive information is a subsection of personal information.

The Privacy Act, including the 13 Australian Privacy Principles ('APP'), regulates the collection of sensitive information and requires a higher level of privacy protection than other personal information. For organisations and agencies subject to the Privacy Act, the collection of sensitive information, including diversity data information, must be:

- in the case of an agency (as defined in Section 6 of the Privacy Act) - reasonably necessary for, or directly related to, one or more of the agencies functions or activities (APP 3.1 of the Privacy Act); to be 'directly related to' one or more of the organisation's functions or activities, a clear and direct connection must exist between the sensitive information being collected and a particular activity;

- in the case of an organisation - reasonably necessary for one or more of the organisation's functions or activities (APP 3.2 of the Privacy Act); and

- in all instances - collected 'by lawful and fair means' (APP 3.5 of the Privacy Act), which means diversity data cannot be collected by spying, hacking, or other illegal means.

In addition to these requirements, organisations may only ask for, and/or collect, individuals sensitive information if the individual consents to the sensitive information being collected, unless a relevant exception as set out in APP 3.4 of the Privacy Act applies (APP 3.3 of the Privacy Act).

Consent to collection

Employers cannot assume that employees automatically agree to participating in diversity surveys. Before collecting and handling sensitive information, including diversity data, employers must obtain express consent.

'Consent' is defined in Section 6(1) of the Privacy Act and, when collecting diversity data, employers must consider the following four key elements of consent:

- Adequate information: Have you told the individual exactly what information you are collecting and what you are going to do with it?

- Voluntary: Has the individual freely made the decision to agree to give you their personal information? Have they been put under any pressure, or told that they cannot, for example, access a particular service without agreeing to part with the requested diversity data?

- Current and specific: Have you asked the individual for their consent recently? And was it for this occasion?

- Capacity: As far as you can tell (acknowledging you may have limited knowledge on which to decide) does the individual have capacity to agree to give you their information?

Guidelines/best practice

The OAIC's Guide to Data Analytics and the Australian Privacy Principles2 ('the Guide') is a useful tool for organisations that engage in data analytics activities, including the collection of diversity data.

Some of the key takeaways from the Guide include the following:

- De-identification of data: Ensure that data is de-identified where possible, noting that information will be considered de-identified only in circumstances where there is no reasonable likelihood of re-identification occurring. If information is considered de-identified, it will generally not be subject to the Privacy Act.

- Collection statements: Ensure collection statements are in place which clearly articulate why diversity information is being sought, how it will be used, and where it will be stored.

- Privacy Impact Assessments: Conduct a Privacy Impact Assessment ('PIA') as a risk management exercise. The purpose of a PIA is to identify privacy risks and to develop strategies to mitigate them. As stated in the Guide, 'the greater the data analytics complexity and higher the privacy risk is, the more likely it will be that a comprehensive PIA will be required to determine and manage its impacts'. While not mandatory for all organisations subject to the Privacy Act, a PIA would assist with the process of streamlining the collection of diversity data which is certainly considered high risk.

- Privacy policy: Have a clear and up to date privacy policy. Under APP 1 of the Privacy Act, organisations must manage personal and sensitive information in an open and transparent way. By having a clearly expressed privacy policy, the complexity of diversity data collection can be broken down to relevant stakeholders.

- Privacy culture: Ensure that there are clear privacy management roles and responsibilities, as well as regular staff training. Embedding a culture of privacy compliance is critical to ensuring the adequacy of diversity data collection.

China

Dora Luo, Partner at Hunton Andrews Kurth, analyses the relevant requirements for the collection of employee data under the various legal regulations in China.

As a general principle under Chinese law, the collection of personal information shall be subject to the consent of the relevant data subjects. According to Standard GB/T 35273-2020 on Information Security Technology - Personal Information Security Specification ('the Specification'), religion and sexuality are considered to be sensitive personal information and are therefore subject to the express consent of data subjects before collection and processing. Please note that the Specification is not legally binding and cannot be used as a direct basis for legal enforcement. However, in practice, the provisions of the Specification may be used as a reference or guideline in enforcement practice, especially for some vague legal provisions without specific requirements. As such, it is suggested that companies comply with the Specification for best practice.

In addition, pursuant to the Personal Information Protection Law (Draft) ('the Draft PIPL'), besides the aforementioned types of personal information, race and ethnicity data is also regarded as sensitive personal information. The Draft PIPL requires data controllers to obtain 'separate consent' from data subjects before processing sensitive personal information and to inform data subjects of the necessity of processing and its impact on data subjects. As it stands, the Draft PIPL has not been officially finalised. Nonetheless, once it becomes effective, it will be considered as the most important law regulating protection of personal information and all provisions will be legally binding.

Singapore

Chester Toh and Joyce Ang, Partner and Associate respectively at Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP, outline what obligations would apply to the collection of employee data for diversity surveys under Singapore's Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (No.26 of 2012) ('PDPA').

The PDPA is the overarching law in Singapore that governs the collection, use, and disclosure of personal data by private organisations, and imposes nine obligations on organisations with respect to the protection of personal data of individuals. There are no specific legal requirements pertaining to the collection of personal data for the purposes of a survey, such as a diversity survey, therefore the general obligations outlined in the PDPA would apply.

From the outset, it should be noted that under Section 4(1)(c) of the PDPA, the obligations in the PDPA do not apply to any public agency in relation to the collection, use, or disclosure of personal data. Accordingly, to the extent that the diversity surveys are directly commissioned by a public agency in Singapore, the obligations in the PDPA would not apply.

'Personal data' is defined in Section 2(1) of the PDPA as data, whether true or not, about an individual who can be identified from that data, or from that data and other information, to which the organisation has, or is likely to have, access. To the extent that the information gathered by the surveying organisation ('the Surveyor') is sufficient to identify the specific individual being surveyed ('the Respondents'), such information is deemed personal data and falls within the purview of the PDPA.

For the avoidance of doubt, personal data that is anonymised by being converted into data that cannot be used to identify any particular individual is not considered personal data for the purpose of the PDPA and is not subject to the provisions and obligations under the PDPA. In this regard, the PDPC Advisory Guidelines for Selected Topics provide some examples of anonymisation, including pseudonymisation, aggregation, data suppression, and data recoding or generalisation. Data would not be considered anonymised if there is a serious possibility that an individual can be re-identified from the data collected, taking into consideration both the data itself or the data combined with other information to which the Surveyor has, or is likely to have, access, and the measures and safeguards implemented by the Surveyor to mitigate the risk of identification. Accordingly, to the extent that personal identifiers in the survey data, such as names, identification numbers, and addresses, are unnecessary for the survey findings, Surveyors can consider excluding such questions from the scope of the survey or ensure that any data collected is anonymised such that the relevant obligations under the PDPA are not applicable.

If the information gathered from the survey includes personal data, a general overview of the obligations applicable to the Surveyor include, but are not limited to:

- ensuring that the Respondents have provided consent to the purpose for which their personal data is being collected, used, and disclosed (also known as the consent obligation);

- ensuring that the personal data collected from the Respondents is not, and will not be, used or disclosed for a purpose to which the Respondents have not provided their consent, or for which their consent has not been deemed (also known as the purpose obligation); and

- procuring that there are sufficient measures in place to ensure that the Surveyor or any other data intermediaries involved in the processing of the personal data of the Respondents are subject to, and comply with, data protection obligations of a similar level in relation to the Respondents' personal data, especially in the scenario where the personal data is being transferred out of Singapore.

Section 28 of the PDPA empowers the Personal Data Protection Commission ('PDPC') to take any such regulatory action as it may deem necessary against an organisation if it is satisfied that an organisation is non-compliant with its obligations under the PDPA in relation to the collection, use, disclosure, and processing of personal data in its possession and control. Such regulatory actions include giving directions requiring the organisation to:

- stop any collection, use, or disclosure, or destroy personal data in contravention of the PDPA;

- direct a dispute between an individual and the organisation arising in connection with the individual's personal data (in respect of which a complaint has been made to the PDPC) to be referred to mediation, provided that the individual complainant has consented to such dispute being referred to mediation; or

- pay a financial penalty as the PDPC may see fit for any non-compliance with the organisation's obligations.

For completeness, we wish to also highlight that the Personal Data Protection (Amendment) Act 2020 ('the Amendment Act') was passed in Parliament on 2 November 2020 and partially came into effect on 1 February 2021. The key amendments that were introduced in the Amendment Act include:

- introducing a mandatory data breach notification;

- widening the scope of 'deemed consent';

- facilitating data portability;

- introducing new offences for the egregious mishandling of personal data; and

- increasing the financial penalties for non-compliance with the provisions of the PDPA.

Surveyors should be aware of these further developments and ensure compliance with the newly introduced regulations where applicable.

As mentioned, there are no specific guidelines in relation to the conducting of surveys or market research. However, there are general guidelines issued by the PDPC for private organisations collecting, using, and disclosing data.

Japan

Hiroyuki Masuda, Lawyer at One Asia Lawyers, outlines the specific rules that are applicable for the collection of data relating to race, religion, sexuality, health, and age, as well as a number of recommendations and best practices for organisations.

The Act on the Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of 2003 as amended in 2015) ('APPI') does not define the term 'sensitive data'; however, there is a similar concept under the APPI, in the form of 'special care-required personal information'.

'Special care-required personal information' means personal information comprising a principal's race, creed, social status, medical history, criminal record, the fact whether a person has been a victim of crime, or other descriptions prescribed by the Cabinet Order on APPI as those of which the handling requires special care so as not to cause unfair discrimination, prejudice, or other disadvantages to an employee (Article 2(3) of the APPI).

Those descriptions prescribed by the Cabinet Order under Article 2(3) of the APPI shall be those descriptions which contain any of the matters set forth in the following (excluding those falling under an employee's medical record or criminal history):

- having physical, intellectual, and/or mental disabilities (including developmental disabilities), or other physical and mental functional disabilities prescribed by the rules of the Personal Information Protection Commission ('PPC');

- the results of a medical check-up for the prevention and early detection of a disease conducted on a principal by a doctor engaged in duties related to medicine;

- guidance for the improvement of the mental and physical conditions, medical care, or prescription given to a principal by a doctor based on the results of a medical check-up or for reasons of the disease, injury, or other mental and physical changes;

- an arrest, search, seizure, detention, prosecution, or other procedure related to a criminal case being carried out against a principal as a suspect or defendant; or

- an investigation, measure for observation and protection, hearing and decision, protective measure, or other procedure related to a juvenile protection case being carried out against a principal as a juvenile delinquent or a person suspected thereof under Article 3(1) of the Juvenile Act (Act No. 168 of 15 July 1948.

Therefore, race/ethnicity, religion, and disabilities would be regarded as 'special care-required information', while sexuality, parenting, and age would not.

The major difference between normal 'personal information' and 'special care-required information' is the requirement for collection and processing. While it is not necessary to obtain the consent of an employee to acquire the personal information (notification of specified purpose is required), it is necessary to obtain an employee's prior consent to acquire special care-required personal information.

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan recommends that the employer must pay careful attention when it asks candidates to describe in the application form and to explain at job interviews the following matters:

- matters which are not attributable to a candidate such as:

- matters related to legal domicile and place of birth;

- matters related to family (occupation, relationship, state of health, clinical history, educational background, income, and assets);

- matters related to housing conditions (layout, number of rooms, types of residence, and surrounding facilities); and

- matters related to living conditions and family background; and

- matters that relate to a candidate's discretion, such as:

- religion;

- political affiliation or views;

- views on life and creed;

- persons whom a candidate respects;

- labour union (including membership and activity history);

- social activism, including student activism; and

- a candidate's preferred newspaper, magazines, or their favourite book, as asking this information will likely lead to discrimination in the job selection process.

Also, the employer should pay careful attention not to conduct the following in the selection of candidates:

- personal background investigations; and

- medical examinations which are not necessary, reasonable, and objective in the selection of candidates.

As such, it might be the best practice not to collect special care-required information, such as race/ethnicity or religion, without reasonable reason. But, usually, the age of candidates will be asked as non-special care-required information.

Kensaku Takase and Aya Takahashi, Partner and Associate respectively at Baker McKenzie, provide further insight on the consent requirements for the collection of sensitive personal data in Japan.

When gathering most forms of personal data, the requirements under Japanese privacy law are fairly relaxed and, as long as the data subject is given information on what is being gathered and how it will be used, the requirements will be fulfilled.

However, Japanese privacy law does get stricter where there may be a transfer of the personal data to a third party inside or outside of Japan, or sensitive personal data is involved.

For data classed as 'sensitive personal data', also known as 'special care-required personal information', opt-in consent from a data subject will be required before it can be gathered and processed. Note that 'age' is not specifically mentioned as a category of sensitive personal data in Japan, and there is no specific guidance from the PPC on this.

As consent is required, making sure that this is obtained in a valid manner is important. According to a guideline published by the PPC, how such consent is gathered really depends upon the nature of business and of the relationship between the data controller and the data subject. In practice, if, for example, it is an employer/employee relationship, then the employer could use written agreements or internal electronic systems. If it is a hospital/patient relationship, then a consent form of some kind, paper based or electronic, may be appropriate. If the information is being gathered in a purely online environment, then an opt-in arrangement where the data subject is given access to the details of the processing will be important. Additionally, if a data subject is 15 years of age or under, consent from a person who has parental authority will be required.

Hong Kong

Pattie Walsh, Jeannette Tam, Stephanie Wong, Diana Purdy, and Jenny Kwan, Partner, Senior Managing Associate, Managing Associate, Consultant, and Associate respectively at Bird & Bird, provide an overview of the relevant requirements for employers looking to collect the personal data of their employees for the purpose of completing a diversity survey.

Excessive data

Under the Data Protection Principles ('DPPs') of the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (Cap. 486) as amended in 2012 ('PDPO'), an employer may collect personal data from an employee provided that the collection of the data is necessary for, or directly related to, a human resource or function of the employer and that the data is not excessive in relation to the purpose. This includes using the methods of data collection that are the least privacy-intrusive. Employers should therefore consider whether it is necessary for the name of the employee to be linked to the data being collected, as this may present a risk that it is excessive for the purpose for which it is being collected.

Although contravention of the DPPs is not an offence, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data ('PCPD') may issue an enforcement notice for the employer to take remedial steps. Failure to comply with an enforcement notice is an offence which may result in imprisonment and/or a fine.

Under the Code of Practice on Human Resource Management ('the Code') issued by the PCPD, it is expected that an employer would need to collect less personal data relating to contract staff compared with data collected in respect of employees. The Code is not a legally binding document, but if there are any challenges from an employee in relation to their data privacy rights, the PCPD will take into consideration whether the Code has been adhered to.

Data access and correction

Under the PDPO, employers have an obligation to provide access to, and correction of, an employee's personal data.

Under the Code, it is recommended that the employer explicitly provide:

- information on an individual's right of access to, and correction of, their personal data; and

- the contact details of the person to whom any such request may be made.

Security of personal data

Under the PDPO, the employer has the obligation to take all practicable steps to ensure that the personal data is protected against unauthorised or accidental access or use, having particular regard to the kind of data and the harm that could result should unauthorised or accidental access or usage occur.

Erasure of personal data

Under the PDPO and the Code, the employer has an obligation to take all practical steps to ensure that the personal data is not kept longer than is necessary to fulfil the purpose for which the data is to be used. The PDPO does not specify a fixed duration of time for which an organisation can retain personal data as it recognises that each organisation as its own specific business needs.

India

Vinod Joseph and Suchita Ambadipudi, Partners at Argus Partners, unravel the distinctions between personal and sensitive information, while also outlining the legal requirements for the collection of personal information in India.

India's data privacy regime can be found in the form of the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011 ('the SPDI Rules'), which have been framed under Section 43A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 ('the IT Act').

There are no Government approved standards, best practices, or guidelines on the collection of personal information as a part of a diversity survey. Nonetheless, 'personal information' is defined under Rule 2(i) of the SPDI Rules as any information that relates to a natural person, which, either directly or indirectly, in combination with other information available, or likely to be available, with a body corporate, is capable of identifying such person.

The SPDI Rules also provide an exhaustive list of certain types of personal information which would be treated as sensitive personal information. Data pertaining to sexuality and disabilities would be considered sensitive personal information under the SPDI Rules, and data pertaining to race/ethnicity, religion, parenting, and age would be personal information, but not sensitive personal information.

The SPDI Rules protect personal information which is collected by an individual or a person who is involved in commercial or professional activities. A 'body corporate' is defined under Section 43A of the IT Act as 'any company [including] a firm, sole proprietorship, or other association of individuals engaged in commercial or professional activities'. Therefore, an individual or a person who is not engaged in commercial or professional activities would fall outside the ambit of the SPDI Rules. Neither the IT Act nor the SPDI Rules define the terms 'commercial' or 'professional'. The Government of India issued a clarification, dated 24 August 2011, outlining that Rules 5 and 6 of the SPDI Rules pertaining to the collection and disclosure of personal information do not apply to corporates providing services related to the processing of sensitive personal data or information to any person under a contract, unless they provide such services directly to the data subject under a contract.

The key principles relating to the collection of personal information are:

- The body corporate or data fiduciary that collects personal information is required to publish a privacy policy on its website for the handling of personal information (Rule 4 of the SPDI Rules). The policy must provide for a clear and easily accessible statement of its practices and policies, type and purpose for the collection of personal information, and the security practices undertaken.

- While collecting personal data, the data subject should be informed of the following:

- that their personal data is being collected;

- the purpose for which the personal data is being collected;

- the intended recipients of the personal data;

- the fact that the data subject has the right to refuse to provide the data; and

- the name and address of the agency that is collecting the personal data and of the agency that will retain such personal data (Rule 5(3) of the SPDI Rules).

- The personal data collected shall be used for the purpose for which it has been collected (Rule 5(5) of the SPDI Rules).

- The data subject has the right to review their personal data and have it corrected or amended if feasible (Rule 5(6) of the SPDI Rules).

- The data subject has the right to refuse to provide the data or withdraw consent at any time (Rule 5(7) of the SPDI Rules).

- A body corporate may transfer personal information to any other body corporate or any person located within or outside India that can ensure the same level of data protection that is adhered to under the SPDI Rules. Such transfer will be permitted if the data subject has consented to the transfer, or if the transfer is necessary for the performance of a lawful contract between the body corporate and the data subject (Rule 7 of the SPDI Rules).

- A body corporate is required to adhere to reasonable security practices and procedures under the SPDI Rules. A body corporate will be deemed to have fulfilled reasonable security practice standards under the SPDI Rules by implementing the IS/ISO/IEC 27001 standard on Information Technology Security Techniques - Information Security Management System Requirements (Rule 8 of the SPDI Rules). The SPDI Rules require the security standard adopted to be certified or audited on a regular basis by entities through an independent auditor, duly approved by the Central Government (Rule 8(3) of the SPDI Rules).

In addition to the principles mentioned above, the SPDI Rules require the obtaining of consent prior to the disclosure of sensitive personal information. Since the categories of aforementioned data only pertain to the collection of personal data, we shall not delve into this aspect any further.

Angela Potter Privacy Analyst

Comments provided by:

Katherine Sainty Director

[email protected]

Sainty Law, Sydney

Natasha Singh Graduate Lawyer

[email protected]

Sainty Law, Sydney

Dora Luo Partner

[email protected]

Hunton Andrews Kurth, Beijing

Chester Toh Partner

[email protected]

Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP, Singapore

Joyce Ang Associate

[email protected]

Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP, Singapore

Hiroyuki Masuda Lawyer

[email protected]

One Asia Lawyers, Tokyo

Kensaku Takase Partner

[email protected]

Baker McKenzie, Gaikokuho Joint Enterprise, Tokyo

Aya Takahashi Associate

[email protected]

Baker McKenzie, Gaikokuho Joint Enterprise, Tokyo

Pattie Walsh Partner

[email protected]

Bird & Bird, Hong Kong

Jeannette Tam Senior Managing Associate

[email protected]

Bird & Bird, Hong Kong

Stephanie Wong Managing Associate

[email protected]

Bird & Bird, Hong Kong

Diana Purdy Consultant

[email protected]

Bird & Bird, Hong Kong

Jenny Kwan Associate

[email protected]

Bird & Bird, Hong Kong

Vinod Joseph Partner

[email protected]

Argus Partners, Mumbai

Suchita Ambadipudi Partner

[email protected]

Argus Partners, Mumbai

1. Available at: https://www.dca.org.au/inclusion-at-work-index

2. Available at: https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/guidance-and-advice/guide-to-data-analytics-and-the-australian-privacy-principles/#part-1-introduction-and-key-concepts